Do we solve it today or tomorrow?

A topic of attention for food and nutrition sustainability of the future global population is undoubtedly arable soil and its quality. Even more important will be to understand how to use it to ensure the resource for future generations. Biomimicry can guide us on this sustainable path.

Es un tema que aparece tangencialmente a nuestras vidas, tal vez porque conforme pasa el tiempo nos concentramos en áreas urbanas y así perdemos progresivamente nuestra relación con el campo y la naturaleza. De vez en cuando, si, al salir a almorzar un domingo fuera de la ciudad, al ir en un avión cruzando una porción terrestre, al atravesar los campos en un tren o al salir de vacaciones somos capaces de contemplar la maravilla de las áreas rurales, su diversidad (no en todos los casos) y sus oportunidades. Nuestra vista cruza bosques, páramos, ríos, desiertos y lagunas mientras seguimos en movimiento. Y esa imagen progresiva nos encanta y nos relaja. En algún momento inclusive nos lo cuestionamos: El vivir en el campo, lejos del estrés y la congestión de las ciudades, cultivar alimentos, criar ganado y en resumen mejorar nuestro bienestar. Al ver a los agricultores labrando, trasladando las vacas, sus casas sacando humo por las chimeneas y produciendo alimentos de diversas plantas y animales nos generemos una buena foto para volver a casa. Allí, pocas horas después de haber llegado la idea y la imagen se disipa. Más preocupante aun, no logramos relacionar que aquel campo de girasoles, el agricultor, la vaca, el tractor, el suelo que lo contiene y el agua que serpentea el cultivo son esenciales para la subsistencia urbana.

La superficie terrestre comprende 149 millones de kilómetros cuadrados, de los cuales un 71% corresponde a tierra habitable, 10% a glaciares y un 19% a tierras áridas (desiertos arenosos y de sal, rocas expuestas, playas y dunas). Gran parte del éxito del primer grupo es el tener un suelo apropiado para la agricultura, el crecimiento de bosques frondosos e inclusive para poder construir las ciudades en que vivimos. Básicamente, es el soporte sobre el cual se cimientan nuestra civilización y gran parte del mundo natural terrestre. Su deterioro en cambio puede tener un efecto muy negativo para el bienestar terrestre. Por un lado, si la deforestación continua (entre 1700 y 2016 los bosques han disminuido desde un 57% de la tierra habitable hasta un 38% en 2018) el suelo se erosionará y no podremos contar con recursos que sirven diferentes propósitos, entre ellos absorber el dióxido de carbono que emiten varios de nuestros diseños a través de los árboles, flores y plantas. Un gran reto para las décadas por venir es como podemos conservar y reforestar algunas regiones del planeta. Por el otro, si nuestras prácticas agrícolas, especialmente aquellas basadas en el monocultivo continúan en las siguientes décadas a través del empleo de fertilizantes y pesticidas basados en combustibles fósiles y de métodos como la labranza intensiva. el suelo se hará cada vez más árido y nuestra seguridad alimentaria será cada vez más frágil y poco resiliente. El gran problema en este caso es la siguiente paradoja: La agricultura moderna nos permite alimentar un gran porcentaje de la población humana (7.8 billones de habitantes para 2020 en comparación a tan solo 1 billón en1900), aumentando su productividad a través del uso insostenible del suelo y de recursos no renovables tal como el agua dulce. Sin embargo, sin esta práctica los alimentos escasearían, sus precios se dispararían y no sería posible entregar comida nutritiva a la mayoría de las personas. ¿Como podemos entonces lograr un equilibrio para solucionar el corto y largo plazo a la vez?

Yet, not all the news are negative. At least our goal at Greenroad is to provide solutions within realistic possibilities. A very interesting study carried out by Daniel Evans recently shows us that we still have time to make a positive impact change to protect fertile lands. Through a soil analysis in 255 locations around the world, the study reviews how many years it would take to erode 30 centimeters of fertile soil (black soil) based on current erosion rates for three scenarios: Soils without vegetation as the worst case scenario, soils that are managed with conventional practices and finally soils that are worked with sustainable practices for conservation purposes. Results are surprising: In the first case, 34% of the vacant soils could last 100 years before being completely eroded. As for land with conventional uses that includes monocultures, 16% of them would last 100 years. Finally, in the scenario of soils managed with conservation objectives, 7% of the soils can last for 100 years. The study also shows that 39% of these soils would last more than 10. 000 years, generating a very optimistic scene. Hence, we have a great opportunity to solve our paradox.

Biomimicry, forest conservation and agriculture are closely linked, since we are intrinsically working with nature. Rather than emulation, we face in this case a minimal intervention to increase the benefits for human beings without risking survival. From a global point of view, the first advice from the biomimetic perspective is to change the extractive vision that we have in agriculture, for a regenerative one in which we produce food while conserving the diversity of nature. Second, we must prefer local production over that of other countries, which implies a larger carbon footprint among other drawbacks. Third, we must perform reforestation on forest and bare lands to increase fertile soil.

In order to use soils for food production without damaging its composition, two alternatives can be considered : First, groups of people who want to make the countryside their home and wish to subsist with what they produce and sell surpluses to local markets. In this case, permaculture and agroecology present excellent opportunities, with successful stories ranging from 0. 5 to 10 hectares. They also include profits of 40% with incomes between 150. 000-250. 000 USD per hectare (Fortier, 2014). Yet, this does not solve the problem of global nutrition. Secondly, the author Jocanovic (2017) recommends “integrated agriculture”, for larger scales. This is defined by European standards as a system where organic food, fiber, balanced food and renewable energy are produced using resources in a sustainable way , avoiding harmful agents.

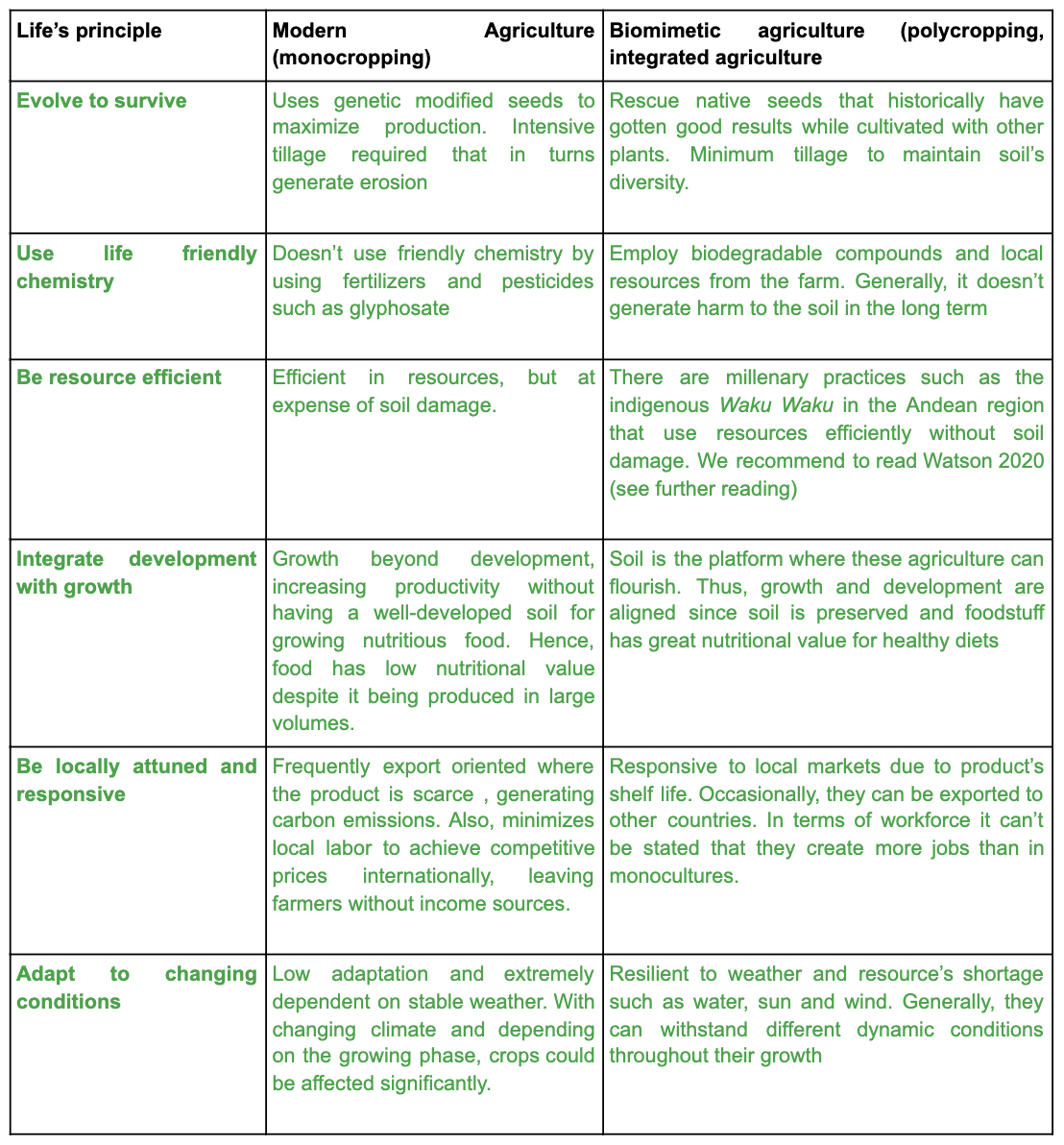

As the reader can deduct, there are viable solutions to feed ourselves and prevent soil erosion. In this table we present some ideas of how agriculture models follow or not life’s principles . We hope they are useful!

We recommend the following sources for further reading

- Baumeister, D (2014). Biomimicry resource handbook.

- Fortier , J.M. (2014) . The market Gardener : A successfull grower handbook for small scale organic farming. New society publishers, Canada.

- Evans D.L et al (2020). Soil lifespan and how they can be extended by land use and management change. Environmental research letters, Vol 15 0940b2.

- Jocanovic (2019). Biomimicry in Agriculture: Is the ecological system design model the future Agricultural Paradigm. Journal Agricultural Environmental Ethics. Vol 32, pp.789- 804.

- Watson, J (2020). Lo-Tek. Design by radical Indigenism. Waru Waru Agricultural terraces of the Inca, Peru. Taschen, New York.